It was the job of the 19th century publisher to contract with an author to write the book, to arrange for a printer and bindery and, finally to market and sell the book. Memoirs are an excellent example of how a 19th century book went from conception by the author and publisher to enjoyment by the reader. Because Grant and Clemens were involved in Memoirs, there is a wealth of information regarding the creation of Memoirs scattered throughout the histories of both 19th century American luminaries.

As part of Clemens’s sales pitch to Grant, he promised that Memoirs would be sold by subscription. Clemens had sold all of his books by subscription (Friedman, 2004, p. 66). Before Clemens began Charles L. Webster & Co, he “was actively involved in marketing of his books, he paid attention to the cost of production and to the illustrations, making sure the final product would be appealing, or at least intriguing, to the public” (id.). In 1879, with the publication and subscription sales of Clemens’ novel, A Tramp Abroad, Clemens netted only $32,000 of the $218,000 total revenue (id. p. 67). Armed with that knowledge, in 1884, Clemens formed a publishing company with his niece’s husband, Charles L. Webster, to publish his own works and reap the financial benefit for himself (id. p. 68). The company was Charles L. Webster & Co. At the helm was Charley Webster, with Clemens in the background pulling the strings. After securing the Grant contract, Charley Webster went about making the necessary arrangements to publish a book for subscription. Even before Grant had finished writing Memoirs, Charley had hired 10,000 salespeople to sell it (id.).

In 19th century America, there were two ways to sell new books: door-to-door by subscription or in a retail store. An average subscription book cost $5.00 to $7.00. Retail books cost about $3.50 (Friedman, p. 61). Books that were sold by subscription were not available in retail bookshops. Further, book agent contracts expressly prohibited book agents from selling a subscription to a retail bookshop (id.).

After the Civil War, book salespeople were called “canvassers” or “agents.” A book agent was hired by a publisher to sell books by subscription, “that is, to take orders for delivery at a later date” (Friedman, p. 59). Books sold by subscription were “often long, running 600 to 700 pages, to give readers ‘their money’s worth’” (id.) By the last quarter of the 19th century, most subscriptions were religious books, self-help guides, and Civil War related books. The benefit to the publisher of using book agents and canvassers was to transfer the risk onto the book agents, who paid their own expenses and worked for commission. Surprisingly, a number of canvassers were women (id.).

As publisher, Webster travelled the country hiring agents to manage teams of canvassers. Webster hired 16 “general agents and roughly 10,0000 canvassers” to sell Memoirs (Friedman p. 69). Clemens instructed Webster to hire Civil War veterans. Clemens believed that it “would be harder for prospects to turn away, given the subject matter of the book, and who would be encouraged to wear their Grand Army badges” (id.). Within a month of signing Grant, Webster’s canvassers began sell subscriptions to Memoirs. Later that year, Webster sailed to Europe to arrange for book sellers in England, Germany, Italy and France. (Gen. Grant’s Memoirs. A Large Foreign Sale Assured for the Work, New York Times, October 13, 1885).

It was customary for canvassers to be provided with sales scripts and excerpts from the book to help sell the book and to collect the purchase price after the sale (Friedman p. 62). Clemens directed that all of the canvassers be furnished with a script, which included “a list of truthful & sensible things to say – not rot” (id. p. 69). To train the thousands of subscription agents to sell Memoirs, Webster created a pamphlet titled “How to Introduce the Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant.” The author of the pamphlet was “R. S. Peale & Company.” Some believe that Clemens wrote the pamphlet himself and that “R. S. Peale is a pun for ‘Our Spiel’” (Lambert, p. 12).

Charles Webster contracted with Joseph J. Little & Co. (“J.J. Little”) of New York to print Memoirs. However, when the “work was about half done Webster & Co gave it to someone else” (Held to the Verbal Contract, New York Times, June 5, 1887). Accordingly, J.J. Little sued Charles L. Webster & Co. for breach of contract – Little prevailed and was awarded damages (Held to the Contract, New York Times, May 20, 1888). Perhaps the reason for Webster’s transfer of the printing to another printer was due to Clemens’s complaints that the printing was not being completed fast enough to keep up with the demand of Memoirs:

I ordered 6 sets of plates—and think I remember your taking the responsibility

on yourself of disobeying it. . . .

How many presses?

37 Bullocks?

Then they can do the 300,000 in a single day of 24 hours.

1 Bullock can do it in 40 days.

2 Adams in 40.

Your printers have been using 1 press, & that not all the time.

These 300,000 should all have been ready Sept 1, using a single bullock press.

Lot of presses?—You only needed 1.

Note from Clemens to Webster, 1885 (Michelson, 2006, p. 41).

Before Twain was Twain, he was Samuel Clemens, the printer in Hannibal, Missouri. “Mark Twain’s involvement with the American publishing revolution, which began in earnest when he was a child, absorbed him professionally and imaginatively as a teenager and continued to obsess him as a reporter, storyteller, traveling entertainer, author of books, entrepreneur, and international celebrity” (id., p. 7).

Clemens was obsessed with printing technology – the “Adams” and “Bullocks” referred to above were printing presses. “For book production, the crucial development in Mark Twain’s lifetime was the Adams press, which first reached the American market in 1836” (id., pp. 39-40). The early Adams press was a “bed–and-platen press” which made impressions through forcing two flat surfaces together. An Adams press could produce “a reliable pace of five hundred to a thousand sheets per hour, for book-quality production” (id. at p. 42). Additionally, the Adams press produced excellent illustrations because relief wood and steel engravings could be inserted into the electrotype (id., p. 37). As illustrated below, Memoirs included a number of maps and illustrations which could have been printed on an Adams press. The type appears to be Romana, a transition serif type (Myfonts.com):

Throughout the 1800’s efforts were being made to improve quality of paper and lower cost. It was the mechanization of papermaking, rather than a change of its basic materials that fed, the powered presses and slashed the cost of publication. The availability of inexpensive paper made the subscription price of Memoirs more affordable. Therefore, Memoirs was available to a large and varied audience. Presumably, the paper used in the manufacture of Memoirs was wood-pulp, which was first introduced in 1843 and was the standard at the time (Michelson p. 42).

After the running of the first volume of Memoirs in 1885, it was reported that “1,000 tons of white paper” were used in printing Memoirs (Demand for Gen. Grant’s Book, New York Times, December 3, 1885). In Memoirs advertising material, it was stated that each “volume will contain 600 large octavo pages” (Friedman, p. 70). An “octavo” in traditional printing terms means “a book having eight leaves, or sixteen pages, to the sheet” (Collins, 1912, p. 269). “Octavo” in this case may be a reference to the size of the book. An octavo is a page that is nine inches by six inches (id. at p. 36) – the exact size of the pages in Memoirs. There are no visible watermarks or guide marks on the pages of my set of Memoirs.

The competition was stiff for Civil War materials, especially, the long-awaited publication from Grant. To insure that there was no theft of the proofs from the printers by a “Canadian pirate who can get out ahead of our copyright,” Clemens instructed Webster as follows:

Important

Apl. II.85

Dear Charley—

Stop leaving those proofs on your table—keep them always in your safe. From now till the day of issue, the Canadian emissary will be around (how do you know but you’ve got him in your own employ) seeking to buy or steal proofsheets.

No book ever stood in such peril before as this one. Long before it is out, thieves & bribers will be thick around the printing houses & binderies, ready to buy or steal even a couple of pages & sell to somebody. . . .

How will this do: Mrs. Grant & we (in our proportions) to pay to the printers & binders $3,000 ($6,000 to the two) if on the day of publication no proofs or sheets have escaped; & they to pay us $25,000 each if it can be shown that an escaped proof or sheet got out through their negligence—that is, the negligent one pays. The 3,000 each would enable them to keep watchmen night & day over presses, compositors, binders, stereotypers, &c — & they would have to know their watchman, or they’d be bribed. . . . .

These things are of the very last importance. Give them some share of your instant attention.

Keep your proofs in your safe.

Yrs

S.L.C.

(Webster, pp. 314-315).

Charley must have done his job because Memoirs was, and still is, a success.

Before Grant’s death, “sixty thousand sets of the Personal Memoirs had been ordered by subscription” (Waugh 2003). Grant’s death in July 1885 “so largely and so suddenly augmented the orders for his Memoirs that it seemed impossible to get the first volume printed in time for the delivery . . . J.J. Little had the contract of manufacture, and every available press and bindery was running double time to complete the vast contract” (Paine, p. 816). Webster noted that the “pain and suffering in which the conclusion of the second volume was written attracted universal attention and sympathy” (Gen. Grant’s Memoirs. A Large Foreign Sale Assured for the Work, New York Times, October 13, 1885). On publication day, there were 200,000 copies of Memoirs available for shipment to San Francisco, Chicago, the Midwest, New England, Delaware and Pennsylvania. (Friedman p. 73) Additionally, Webster arranged to ship of Memoirs to Canada, England, and Germany to fill foreign subscriptions. (Demand for Gen. Grant’s Book, New York Times, December 3, 1885).

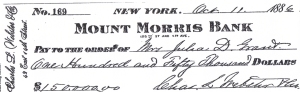

“Much of the profit went to Grant’s widow. . . . In 1886 Charles Webster gave Julia Grant a check for $200,000; the family eventually received a fortune of between $420,000 and $450,000 from sales of Personal Memoirs” (Friedman p. 73)

Image 14

Webster estimated that when Volume II of Memoirs was published that “a check for a sum between $225,000 and $250,000 would be given to Mrs. Grant within the next 30 days” (A Handsome Check for Mrs. Grant, New York Times, January 28, 1886).

Memoirs “sold briskly into the first decade of the 20th century before falling into obscurity by the late 1920s and 1930s. It was no coincidence that Grant’s reputation reached a nadir in those particular decades, as the popular culture celebrated the romantic image of the Confederacy epitomized in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind and immortalized in the movie of the same title” (Waugh 2003, p.11).

When Memoirs was released in 1885, it was an instant best seller, the “reviews were effusive, and many compared the Personal Memoirs favorably with Caesar’s Commentaries” (Waugh, 2003). In addition to the reviews above, Memoirs received praise from 19th and 20th century intellectuals such as Gertrude Stein, Henry Adams and Henry James. “Military comrades, such as former Union General William T. Sherman and former Confederate General Simon B. Buckner, who both who served as pallbearers at Grant’s funeral, were also delighted with the Personal Memoirs” (id.).

Two years after Memoirs was published, Matthew Arnold, an English writer and influential literary critic of the time, wrote a lengthy review of Memoirs and included some personal antidotes of his brief interactions with Grant while Grant was President (Simon, p. 6-7). Arnold’s two part review was published in Murray’s Magazine and reprinted again in 1887. The review was not flattering to Grant’s literary skills. An outpouring of support for Grant and his writing abilities flourished. Clemens was outraged by Arnold’s review. He issued a rejoinder in April 27, 1887 before a reunion of the Army and Navy Club of Connecticut. After rebuking Arnold, Clemens launched into a sales pitch for Memoirs – which resulted in roaring applause from his audience:

General Grant’s book is a great . . . unique and unapproachable literary masterpiece. . . . . when we think of General Grant our pulses quicken and his grammar vanishes: we only remember that this is the simple soldier who, all untaught of the silken phrase-makers, linked words together with an art surpassing the art of the schools, and put into them a something which will still to American ears, as long as America shall last, the roll of his vanished drums and the tread of his marching hosts. (Simon, p. 57).

However, the best review of Memoirs is not from Grant’s contemporaries or historians, it is from the consuming public – Memoirs has never been out of print since its publication in 1885 (Waugh 2009, p. 211).

In 1885, Webster & Co. published only two books: Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant and Huck Finn. Obviously, 1885 was a banner year for the one-year-old publishing firm run by Clemens and Webster. Webster & Co continued to publish works by Clemens and others, including the Memoirs of General Sherman, General Sheridan and General McClellan, and the biography of Pope Leo XIII (Krauss, 2007, p. 161). In 1888, Charley Webster became ill and resigned. He died three years later. Three years after Webster’s death, Charles L. Webster & Co. was insolvent.

In 1885, Webster & Co. published only two books: Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant and Huck Finn. Obviously, 1885 was a banner year for the one-year-old publishing firm run by Clemens and Webster. Webster & Co continued to publish works by Clemens and others, including the Memoirs of General Sherman, General Sheridan and General McClellan, and the biography of Pope Leo XIII (Krauss, 2007, p. 161). In 1888, Charley Webster became ill and resigned. He died three years later. Three years after Webster’s death, Charles L. Webster & Co. was insolvent.

Despite the warm relationship Clemens had had with his nephew Charley Webster, after Webster’s death and the failure of the publishing company, Clemens blamed Webster for the failure and his own subsequent financial problems. Clemens’ vilification of Charles L. Webster led Charles’ son, Samuel Charles Webster, to write a book to vindicate his father. Samuel Webster wrote “Mark Twain attributes the failure of his publishing house, one of the foremost in America, Charles L. Webster and Company, entirely to my father, Charles Webster – who had retired six years before the failure occurred” (Webster, p. vii). Samuel Webster’s book, Mark Twain, Business Man, was a collection of letters between Charley Webster and Clemens. The letters published by Samuel Charles Webster in 1946, spawned a book titled “Hatching ruin” or Mark Twain’s Road to Bankruptcy by Charles H. Gold in 2003. In both books, Charley Webster was vindicated. Whatever Clemens’ financial difficulties were, they were of his own making.

NEXT PAGE →

←PREVIOUS PAGE